Tělo malby / The Body of a Painting

hunt kastner, Prague, 2017

Bodies among images

How easily we forget about our bodies, yet we are surrounded by a plethora of its images – in advertisement, the virtual realm and even in more abstract ways. The image itself becomes a body, an entity of its own, or more precisely it is personalized in a more profound way- what we feel, what we bear or what we fight against is the image we are identified with.

The relation between image and body has, of course, a long history, but right now it may require a new, more serious account. The relation is not only metaphorical – the image is also the body that we share. If we cannot share our self-image, our social and cultural body, there is not much hope in communicating other meanings.

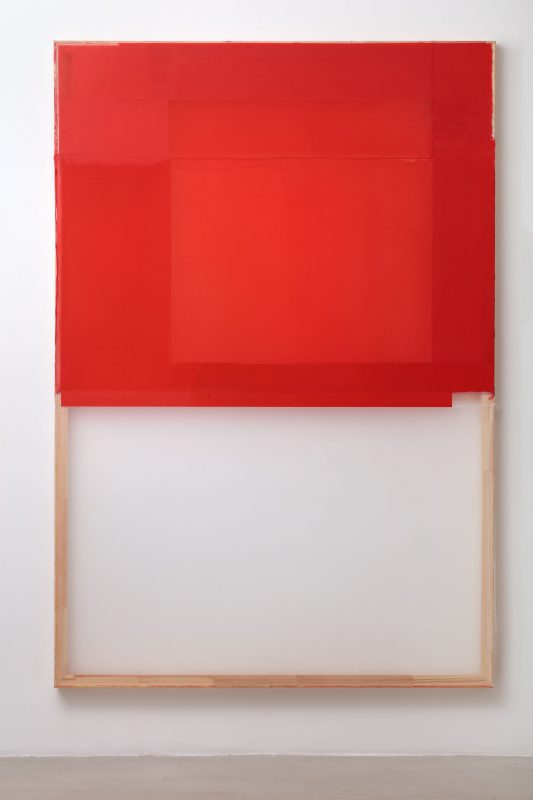

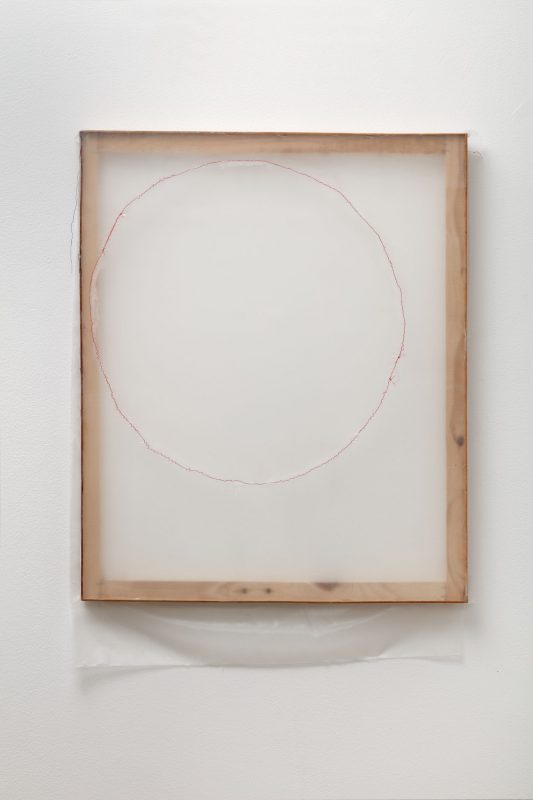

Painting is necessarily carnal or even erotic – it is no accident that it affects our body by its size and verticality, dragging us through the space. If painters invest not in representing something but into the work with the medium itself, it is a type of surgical labour. They are not trying to hide the process or materiality of the painting, make it transparent so that we see only the content. The painting itself is present and all the strokes, gradients, edges and sutures create not only visible shapes but also clusters, sediments and organs.

One of the most interesting concepts elaborated by the philosopher Gilles Deleuze is probably the ‘body-without-organs’. Here Deleuze does not have in mind an actual human body, nor just a metaphorical one. The body represents for him the material, the virtual, which subsequently accepts form and expression – it is the field of the matter and the possible. Our bodies and images are, in such a respect, at least potentially void and therefore pregnant with possibilities. But they are instantly inhabited by our self, our culture and habits. We are becoming ourselves, in the course of which we loose our possibilities and our body-without-organs. Art can deliver us, at least for just for a moment, to the original body.

When I met Jaromír Novotný, he recounted all the specific steps in his work while hanging and moving canvases, display cases or shelves. He set and combined, connected and divided individual pieces in the course of which they gained traction and aesthetic weight. Abstract compositions became figurative, not as singular canvases but within a certain space and in relation to other bodies.

How easily we forget about our bodies and yet we are primarily our bodies, we and our images. When for instance a young girl is becoming a woman, according to Deleuze, the body and the virtual is being inhabited and filled with history, morals and gender. The girl, and her body in general, are not defined by age and sex – it is a body-image not a „real“ body. Bodies are determined by their aptitude for and rates of change, by their ability to cross diverse fields, sensitivities and velocities. We are constantly in the flux of becoming, but we are not only getting older, we can get younger as well – we can go through different places and rhythms, we are able to enter various relations and affect various bodies.

Nonetheless the transformation of the young girl, which for Deleuze still remains a line of escape, representing a certain liberation in the face of the disciplining powers of society, family or economy, now becomes a pinnacle of consumerism and spectacle. The young girl represents the self-image of a commercialized society, in which youth, seduction and even beauty become a matter of labour and consumption, production and distribution. In such a situation art strives to fortify itself against the low and popular on one hand but on the other it willingly accepts the strategies of professionalization and marketing.

All these problems may seem at first to be remote from the abstract and precise work of Jaromír Novotný but in thinking so we would once again forget our bodies. We would be oblivious about all the divisions and cuts, sewing and stretching of the fabric, insertions of objects and organs, inhabiting the body of a painting. Similarly, we are constantly forgetting about the fact that the economical and social pressure applies at first to our bodies. Indeed, our body is complex and multiple, stretching itself in multiple ways between the image and the viewer.

Václav Janoščík

Těla mezi obrazy

Jak snadno zapomínáme na svoje těla. A přitom jsme obklopeni nekonečným množstvím jeho obrazů, reklamních, virtuálních ale i abstraktních. Samotný obraz se stává tělem; přesněji řečeno stává se jím v hlubším slova smyslu. To, co nyní zakoušíme, to, co snášíme, nebo naopak to, vůči čemu se bouříme je náš obraz, se kterým se identifikujeme.

Vztah obrazu a těla má samozřejmě dlouhou historii, ale možná, že přišel čas brát jej jinak a vážněji. Nejde jen o metaforický vztah. Obraz je naším tělem, které sdílíme. Pokud nesdílíme obraz nás samých, naše společenské a kulturní tělo, těžko můžeme komunikovat další významy.

Malba je nutně tělesnou, možná erotickou záležitostí. Není náhodou, že svým rozměrem nebo vertikální polohou působí na naše tělo, táhne nás prostorem. Pokud se pak pak malíři věnují nikoli zobrazování, ale samotnému médiu malby, jde takřka o chirurgickou práci. Již se nesnaží malbu skrýt, zprůhlednit tak, aby zobrazovala určitý obsah. Sama malba je přítomná a jednotlivé tahy, přechody, okraje a švy vytváří nejen viditelné tvary, představují shluky, sedimenty a orgány.

Jedním z nejzajímavějších a možná neobtížnějších pojmů Gillese Deleuze je tělo bez orgánů. Nemá na mysli lidské tělo, ale zároveň nemluví ani metaforicky. Tělo je pro Deleuze látkou, možností, která teprve přijímá formu a výraz. Tělo představuje virtuální a hmotné pole. Ale vždy již je rozryté diferencemi, okraji a změnami, kterým nutně podléhá každá látka. Tím, jak se tělo zdvojuje, rozmezeřuje a praská, stává se organismem, který je funkční, staví se do vztahu k okolí, k ostatním tělům. Naše těla a obrazy jsou v tomto ohledu alespoň potenciálně prázdna a tedy i plná možností. Ale ihned jsou zabydlována, naším já, kulturou, zvyky. Stáváme se sami sebou, spolu s tím, jak ztrácíme možnosti i tělo bez orgánů. Od umění si může slibovat, že nám alespoň v náznaku a na chvíli toto původní tělo navrací.

Když jsem potkal Jaromíra Novotného, vyprávěl mi o jednotlivých tvůrčích krocích a zároveň věšel na zeď a pokládal jednotlivá plátna, i vitríny a police. Stavěl je a komponoval, kombinoval i odděloval tak, že se abstraktní kompozice staly zcela figurálními. Jinými slovy získávaly specifickou hmotnost a tedy i tělesnost. Nikoli jako plátna samotná, ale právě ve vztahu k prostoru a dalším tělům v jeho rámci.

Snadno zapomínáme na svoje těla a přeci jsme především tělesní, my i naše obrazy. Například když se podle Deleuze mladá dívka stává ženou, tělo a možnosti jsou zabydlovány historií, morálkou a genderem. Dívka, ale i tělo obecně, tak není definováno věkem nebo pohlavím (jde vlastně o obraz-tělo nikoli o „skutečné“ lidské tělo). Vymezuje se schopností a rychlostí měnit se, nebo procházet různé prostory a citlivosti. Neustále se můžeme stávat nejen staršími, ale také mladými; můžeme procházet různé prostory a rychlosti; vcházet do různých vztahů a působit na různá těla.

Ale mladá dívka, která ještě pro Deleuze představuje linii úniku, vůči disciplinující společnosti, rodině, či ekonomickému tlaku, se dnes stává centrem konzumu a spektáklu. Mladá dívka je sebeobrazem konzumní společnosti, pro kterou se mládí, svůdnost i krása stávají otázkou spotřeby a práce, (re)produkce a distribuce. Umění se v této perspektivě na jedné straně snaží obrnit proti nízkému a populárnímu, ale na druhé straně ochotně přijímá schémata profesionalizace a marketingu.

Všechny tyto problémy jako by se zdály vzdálené abstraktní a minuciózní práci Jaromíra Novotoného. Ale to opět zapomínáme na tělo. Na dělení a řezy, na sešívání a nové napínání plátna, na vkládání věcí a orgánů, na zabydlování těla plátna; stejně jako zapomínáme na to, že ekonomický a společenský tlak je uplatňován především vůči našemu tělu. Naše tělo je komplikované a zmnožené, napíná se mezi obrazem a pohledem.

Václav Janoščík

info: hunt kastner

Photo: Martin Polák